At the new seafront restaurant overlooking the bay in the tiny resort of Luderitz on the coast of Namibia, tourists are invited to sit out on the balcony, where they can dine on the finest South Atlantic seafood accompanied by vintage South African wines as they take in the views over neighbouring Shark Island.

But little do they know the horrific truth about that view, which the tourist guidebooks describe as ‘stunning’. Shark Island, with its picturesque setting, was the site of the world’s first death camp – the German invention that culminated in the Holocaust of World War II, the greatest mass crime of the 20th century.

Three-and-a-half thousand innocent Africans were liquidated here at the hands of the Germans, decades before the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party, with the tacit sanction of the German emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm II, and his ministers.

As modern diners tuck into lobster and oysters, washed down with chilled Chenin blanc, just yards away beneath the waters lie the bones and rusting iron manacles of the Germans’ victims.

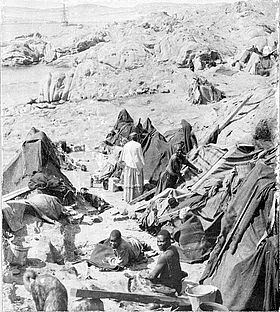

Experiment: The newly invented Kodak roll-film camera was used by wealthier German officers to take home ‘mementoes’ of their time in Namibia

Shark Island is not Namibia’s only gruesome secret. Thousands more bodies are piled in a mass grave under the railway station in the capital Windhoek and more still are piled into a burial pit under the national museum.

The story of the German extermination of the Herero and Nama peoples has been expunged from the history books – and the tourists and scuba divers on the Shark Bay waterfront will find no mention of it in their guides.

But now a new book, The Kaiser’s Holocaust, by David Olusoga and Casper W. Erichsen, lifts the veil on a horrific and little-known episode of history.

More chilling still, the book raises another awful prospect. That the Nazi crimes of World War II were not an aberration, as some have claimed, but emerged from a tradition deeply embedded in the heart of German culture, with its warped beliefs about racial superiority, going back into the 19th century.

Hitler hadn’t been born when the German flag was raised in 1883 on the coast of South-West Africa (as Namibia was then known) – the first conquest of Germany’s African empire.

Significantly, the first Imperial Commissioner was Heinrich Goering, father of Herman Goering, later Field Marshal of the Luftwaffe and the most powerful Nazi after the Fuhrer.

Goering had already planted the seeds of an experiment that would ultimately lead to their genocide

Hitler hadn’t been born when the German flag was raised in 1883 on the coast of South-West Africa (as Namibia was then known) – the first conquest of Germany’s African empire.

Significantly, the first Imperial Commissioner was Heinrich Goering, father of Herman Goering, later Field Marshal of the Luftwaffe and the most powerful Nazi after the Fuhrer.

Until then colonisers had thought Namibia a forbidding place, whose treacherous and fog-bound Skeleton Coast had deterred all but the most intrepid explorers.

But hidden from the gaze of Europeans was a land of enormous beauty – a realm of tall grasses, hot springs and waterholes, where an array of tribes prospered by tending their long-horned cattle and hunting the herds of springbok and wildebeest that roamed the land.

Contrary to the German belief, the indigenous Herero and Nama people were not savages. The Herero had a sophisticated culture, having occupied their ancient lands for centuries, while the Nama – the mixed-race offspring of early Dutch settlers – were ferocious warriors as well as Christians.

Both were more than a match for Goering – an overweight provincial judge with a fondness for dressing up in military uniforms – who fled the colony, his nerves shattered by their relentless insurrections.

However, Goering had already planted the seeds of an experiment that would ultimately lead to their genocide. German South-West Africa was to become a testbed for Lebensraum – the twisted policy of expansion that was to form the heart of Hitler’s ideology.

The ideas were developed in the 1870s by a writer, Friedrich Ratzel, who distorted Darwin’s theory of evolution to argue that migration was essential for the long-term survival of a race. To stop migrating, so the theory went, was to stop advancing and risk being overtaken by other races better fitted for survival.

Teutonic overlord: Kaiser Wilhelm’s African colonies held death camps

What better solution for the Germans living in the crowded cities of the Rhineland than to create a new Germany on African soil? And it was easy to justify the elimination of the local Africans because they were an ‘inferior race’.

However, the Herero and the Nama did not prove quite as ‘inferior’ as the German occupiers thought. For years they stubbornly resisted being driven off their lands into the desert to die, despite huge loss of life at the hands of the Schutztruppe (colonial army) and their ‘cleansing patrols’.

But by 1905 the survivors were weary and weakened. The final straw came when the Kaiser issued an imperial decree expropriating the African lands.

Most of the Africans surrendered and were rounded up into concentration camps to build the colony’s new railways – gruelling work where men were routinely beaten and women workers systematically raped. on one section of the line, two-thirds of the prisoners died in 18 months.

But a sinister new idea was forming in the evil minds of the governors of German South-West Africa. An ‘anthropologist’ was commissioned to investigate the prisoners, who reported that it was of ‘vital importance’ for the success of the German colonial project that those races deemed ‘unfit for labour’ should be allowed to disappear. ‘The struggle for our own existence’ depends on it, he warned.

A sinister new idea was forming in the evil minds of the governors of German South-West Africa

And so the first Holocaust was born. Shark Island – a bleak rocky islet in the harbour outside Luderitz – would become the world’s first death camp and the most feared place on earth for all the black peoples of South-West Africa.

It inspired such terror that on being told he was to be sent there one Herero prisoner fell to the ground bleeding profusely, having drilled his fingers into his neck in a desperate attempt to commit suicide.

Even by the standards of brutality administered by the Germans up to now, what happened inside Shark Island was appalling beyond belief.

A missionary who was one of the first to enter the camp was shocked by what he saw: ‘A woman who was so weak from illness that she could not stand, crawled to some of the other prisoners to beg for water. The overseer fired five shots at her. Two shots hit her: one in the thigh, the other smashing her forearm.’

Another observer tells of the abuse of prisoners forced to carry heavy loads from boats on the shore: ‘on one occasion, I saw a woman carrying a child of under a year old slung on her back and with a heavy sack of grain on her head.

‘The sand was very steep and the sun was baking. She fell down on her face and the heavy sack fell partly across her and partly across the baby. A corporal hit her with a leather whip for more than four minutes, and whipped the baby as well.’

Children at Auschwitz concentration camp. Shark Island, off the coast of the Namibian German colony, was the site of the world’s first death camp – the German invention that culminated in the Holocaust of World War II, the greatest mass crime of the 20th century

The most important witness to the atrocities of Shark Island was the newly invented Kodak roll-film camera, which was used by wealthier German officers to take home ‘mementoes’ of their time there. one surviving snap shows a boy aged about five, his stomach bloated from malnutrition, his only clothing a torn sleeveless vest. In another, an officer poses among the prisoners.

Wearing his military tunic, he stands rigid and poised, walking cane in hand, a group of ragged and frightened African women at his feet.

Many of these photographs of prisoners being mistreated and humiliated were turned into postcards to send back home, often captioned with sardonic comments.

The rape and sexual exploitation of women was not just commonplace but celebrated, and many semi-pornographic images, too, were made into postcards to be posted back to Berlin, Hamburg or Munich.

Unsurprisingly, the inmates started to die in large numbers. Food was so scarce that, according to a witness, when rations were distributed, ‘ prisoners fought like wild animals and killed each other to secure a share’. Others scavenged at the water’s edge searching for limpets, sea urchins or anything else edible.

Those who were not left to die were worked to death, being compelled to carry large stones across the island and drag them into the freezing waters of the bay. They were forced to stand knee-high in the icy sea until they had to be pulled out and their limbs massaged back to life.

After two years, the camp was forced to close – 70 per cent of its inhabitants were dead, and of those still alive a third were so sick the camp commander believed ‘they were likely to die in the near future’.

But this wasn’t before the prisoners had become a resource exploited in the name of medical and racial science in terrible anticipation of the atrocities of the Third Reich.

In one of the local concentration camps, at a place called Swakopmund, women were forced to boil the severed heads of their own people, and scrape the flesh, sinews and ligaments off the skull with shards of broken glass. The victims may have been people they had known or even relatives. The skulls were packed into crates and sent off to museums and universities in Germany.

Most notorious of all was the Shark Island camp physician, Dr Bofinger. He carefully decapitated the bodies of 17 prisoners, including a one-year-old girl. After breaking open the skulls he removed and weighed the brains before placing each head in preserving alcohol and sealing them in tins for export to the University of Berlin.

There they were used in experiments to prove the similarity between the Nama people and anthropoid apes in a terrible prefiguring of the darkest race experiments of Josef Mengele, the Nazi ‘Angel of Death’, who similarly sent body parts from Auschwitz back to Berlin.

Other experiments were conducted on live prisoners. In a spurious bid to determine whether scurvy – an illness caused by poor nutrition – was contagious, Bofinger injected prisoners with arsenic and opium, ‘opening up the bodies’ after they had died. No wonder it was said that anyone who went into Dr Bofinger’s field hospital ‘would not come out alive’.

In 1914, World War I broke out and the following year the South African Army seized the colony which had been such a crucible for evil. Germany’s African empire had ended and, after the war, Namibia became a South African mandate, finally achieving independence in 1990.

Goering dreamed of a German expansion in which the weaker people of the earth were destined to fall prey to the stronger

But Germany’s obsession with eugenics did not end in 1915. A few decades later, the people and ideas that drove this merciless colonial experiment would play a vital role in the formation of the Nazis.

Like his father more than half a century before, Reichsmarschall Herman Goering dreamed of a German expansion in which the weaker people of the earth were destined to fall prey to the stronger.

But there is an even more direct and sinister link between the rise of Nazis and Namibia. One of the veterans of the genocide was a Bavarian senior lieutenant called Franz Xavier von Epp, who spent his life propagating the notion that the German people needed to expand their territory at the expense of ‘lower races’.

In 1922, by then a general, he recruited the young Adolf Hitler into a Right-wing militia in Munich and introduced the future Fuhrer to the elite who would one day control the Nazis.

One of them was Von Epp’s deputy – Ernst Rohm, founder of the notorious Nazi stormtroopers. Through the connection to Von Epp and other old soldiers of the African colonies, Hitler and Rohm were able to procure a consignment of surplus colonial Schutztruppe uniforms.

Designed for warfare on the savannah of Africa, the shirts were golden brown. The Nazi thugs who wore them were thenceforth known famously as the Brown Shirts. It’s no wonder that in countless pictures and propaganda films, Hitler and Von Epp stand side by side.

Not long ago, Germany’ s Development Minister Heidemarie Wieczorek-Zeul travelled to Namibia to ask for forgiveness, using the term ‘genocide’ to describe the German treatment of the Herero and Nama.

A decent gesture, you might think. But her act was not well-received at home and condemned in the German Press. And she made not a single mention of the existence of the Namibian death camps.

More than a century on, the terrible events that took place at Shark Island, and their link to the rise of the Nazis, remain a sordid secret that modern Germany, it seems, still cannot bring itself to acknowledge.

The Kaiser’s Holocaust: Germany’s Forgotten Genocide And The Colonial Roots Of Nazism by David Olusaga and Caspar W. Erichsen (Faber, £20).

Read more: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1314399/Hitlers-Holocaust-blueprint-Africa-concentration-camps-used-advance-racial-theories.html#ixzz3p1wsq9iK

Follow us: @MailOnline on Twitter | DailyMail on Facebook